Collect

I Love a Cat

photography

Size 100cm X 100cm

Price Not Set | Contact us to inquire about artwork status and collection availability

Certificate

M2025PTY000001PA

Artist

潘欣頌

Creation Year

2025

Condition Status

Well

Supplier

POST WINGS

Introduction

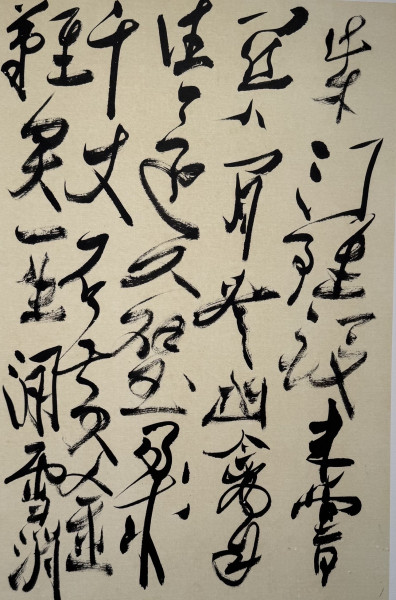

Facing Bu Zi's "Four Screens of Zen Master Qinggong's Poetry," the viewing style of Bai Shiming does not seek the authoritative interpretation of the textual meaning but instead turns the gaze towards the very act of "watching" itself. Here, cursive script is no longer merely a style of writing but an aesthetic of action existing at the edges of language—both present and absent in the meaning of words. The lines from Bu Zi are intense, swift, and indulgent, splattering a free flow of inner "qi." He does not just write poetry but reconstructs the site of poetry's emergence through calligraphy.

Bai Shiming emphasizes that "writing" is not a mere repetition of meaning but an immediate practice intertwined with "body and time." Though Bu Zi was taught by ancient masters, he refuses to adhere to tradition; he wields brush and ink like a sword, traversing the traditional trajectory of Eastern calligraphy to evoke the ultimate tension of individual existence. In this cursive script, the observer is not just a reader but a participant dancing with their sensory body and the ink marks. Bai Shiming would say: this is not calligraphy, but Zen; it is not text, but the Dao—each stroke of the brush is a deep touch and response to the "Dao." Bu Zi, through writing questions, returns calligraphy to its inherent poetic and philosophical nature.

Bai Shiming emphasizes that "writing" is not a mere repetition of meaning but an immediate practice intertwined with "body and time." Though Bu Zi was taught by ancient masters, he refuses to adhere to tradition; he wields brush and ink like a sword, traversing the traditional trajectory of Eastern calligraphy to evoke the ultimate tension of individual existence. In this cursive script, the observer is not just a reader but a participant dancing with their sensory body and the ink marks. Bai Shiming would say: this is not calligraphy, but Zen; it is not text, but the Dao—each stroke of the brush is a deep touch and response to the "Dao." Bu Zi, through writing questions, returns calligraphy to its inherent poetic and philosophical nature.

Video Intro

None

Exhibition Resume